Accelerating Ethereum with Autoprecompiles

- Published on

- Authors

- Name

- powdr labs

Accelerating Ethereum with Autoprecompiles

Since our last update on autoprecompiles, we have been busy evaluating the technique on a host of benchmarks, asking:

- How do autoprecompiles stack up against commonly used manually written precompiles? Can we make them obsolete and eliminate a huge amount of engineering effort and security risk?

- What do autoprecompiles add on top of manually written precompiles on real-world workloads, such as Ethereum block verification?

Let's dive in!

A brief recap of autoprecompiles

In a nutshell, autoprecompiles work by taking a basic block, merging all instruction circuits into one monolithic circuit. This enables several effective optimizations, such as removing redundant memory accesses and constant propagation. The process is explained in more detail in a previous blog post as well as this talk.

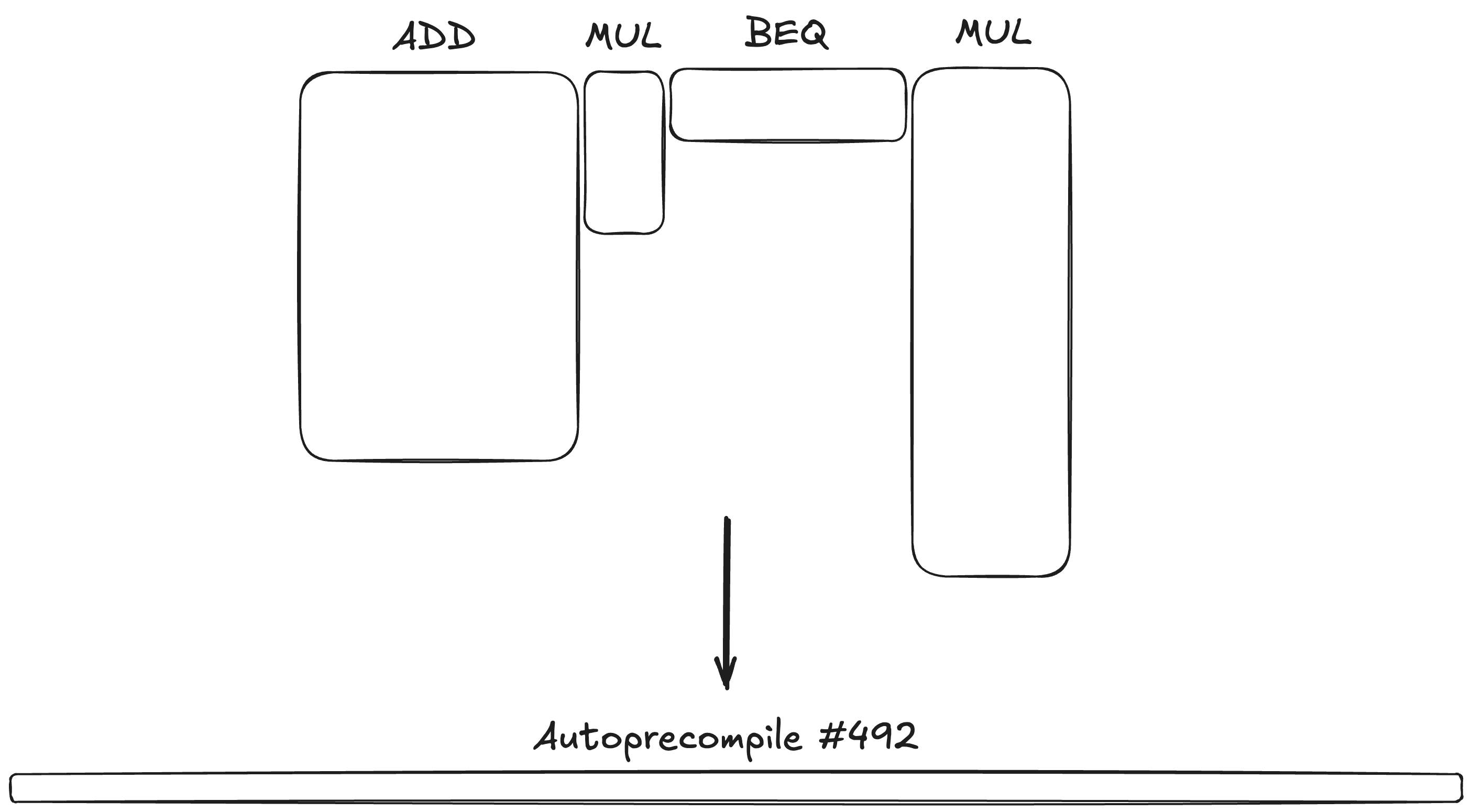

In a zkVM like OpenVM, each instruction has its own trace table, where the number of columns depends on the instruction, and the number of rows equals the number of times this instruction was executed. An autoprecompile essentially adds another table, which proves the correct execution of the entire basic block. This table tends to be wider and has one row for each time the basic block is called:

Because of the optimizations, the total trace area is typically several times smaller. This translates pretty well to proving time! However, depending on the proof system, the increase in the number of columns can lead to an increase in verification time, which hurts recursion time. For this reason, we report the end-to-end proving time, including recursion.

In summary, the tradeoffs are:

- A smaller trace area leads to faster proofs in the first layer.

- The number of segments (a.k.a. shards) tends to become smaller, reducing verification / recursive proving time.

- The increased number of columns does hurt verification / recursive proving time.

Overall, for frequently executed basic blocks, the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. Note also that Succinct has published work that removes the per-column cost of the verifier, promising to eliminate the third bullet point.

Comparisons to manual precompiles

How do our automatically generated precompiles compare to manually written ones? We looked into this in a previous blog post, where we compared OpenVM's Keccak precompile to autoprecompiles. Since then, we have tested our approach against many other precompiles, and we have learned a lot!

In what follows, we report single-CPU proving time (using an Intel® Xeon® Gold 5412U), including recursion unless otherwise noted.

Keccak

We reproduce the Keccak experiment with the newest version (based on OpenVM 1.3). The benchmark computes 25,000 Keccak hashes.

| Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than software | Times slower than manual precompile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | 49 | 866.00 | 1.00 | 10.05 |

| Manual precompile | 4 | 86.15 | 10.05 | 1.00 |

| Autoprecompiles | 3 | 76.88 | 11.26 | 0.89 |

Autoprecompiles perform better than OpenVM's manually written precompile (which is a thin wrapper around Plonky3's Keccak precompile)!

Looking into the constraints, they work completely differently: While the manually written precompile bit-decomposes the Keccak states, the autoprecompiles heavily rely on lookups.

SHA256

In this benchmark, we compute 80,000 SHA256 hashes:

| Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than software | Times slower than manual precompile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | 44 | 740.50 | 1.00 | 15.44 |

| Manual precompile | 2 | 47.97 | 15.44 | 1.00 |

| Autoprecompiles | 2 | 107.59 | 6.88 | 2.24 |

Autoprecompiles achieve a significant speedup here, which comes close to the performance of the manually written precompile.

Elliptic Curve Operations

In this benchmark, we perform a series of elliptic curve scalar multiplications.

Here, we noticed something interesting. Part of the acceleration of the manual precompile comes from the fact that it makes use of hints: Instead of computing, say, the inverse of a field element, the program can receive the result as an untrusted input from the prover and test that it is in fact the requested inverse. OpenVM has an API to supply hints to Rust code directly, without the need to implement a new circuit.

For this reason, we tested two variants:

- Unmodified

k256: This program uses thek256library out of the box, which internally uses projective coordinates and computes inverses in software. - Hint-accelerated

k256: Here, we use hints to accelerate base field inverses and switch to using the affine representation of elliptic curve points.

Note that while there was some manual work involved in preparing the hint-accelerated variant, the amount of work and security risk is still small compared to having to write a new zkVM circuit. In particular, there is no need for the programmer to specify constraints - doing this modification requires patching only the library written in Rust.

Unmodified k256:

| Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than software | Times slower than manual precompile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | 59 | 1122.48 | 1.00 | 62.64 |

| Manual precompile | 1 | 17.92 | 62.64 | 1.00 |

| Autoprecompiles | 4 | 306.80 | 3.66 | 17.12 |

Hint-accelerated k256 (Rust changes, no custom circuits):

| Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than software | Times slower than manual precompile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | 24 | 451.48 | 1.00 | 25.19 |

| Manual precompile | 1 | 17.92 | 25.19 | 1.00 |

| Autoprecompiles | 2 | 117.78 | 3.83 | 6.57 |

We draw the following conclusions:

- There is a 2.5x speedup from the hint-acceleration

- In both experiments, there is a >3.5x speedup from applying autoprecompiles.

- Hint-acceleration and autoprecompiles are orthogonal optimizations: Combining both yields a close to 10x speedup over the original software run!

- The manually written precompile is still a lot faster. We suspect that this is because a big chunk of the computation could still be accelerated by more hints, such as the modular reduction when doing a base field multiplication.

ECDSA

Building on the previous experiment, we implemented an ECDSA public key recovery algorithm using field inverse hints and compared it to OpenVM's manual precompile:

| Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than software | Times slower than manual precompile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | 34 | 659.08 | 1.00 | 32.31 |

| Manual precompile | 1 | 20.40 | 32.31 | 1.00 |

| Autoprecompiles | 2 | 176.67 | 3.73 | 8.66 |

As the ECDSA public key recovery computation is dominated by scalar multiplications, the results are similar to those of the previous section.

U256

In this experiment, we perform a matrix multiplication using 256-bit integers.

| Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than software | Times slower than manual precompile | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | 34 | 636.84 | 1.00 | 1.72 |

| Manual precompile | 22 | 369.45 | 1.72 | 1.00 |

| Autoprecompiles | 2 | 83.33 | 7.64 | 0.23 |

In this benchmark, autoprecompiles are more than 4 times faster than the manually written precompiles!

Ethereum block verification

After having analyzed a few common workloads in isolation, it is time to look into a real-world use case: Verifying Ethereum blocks.

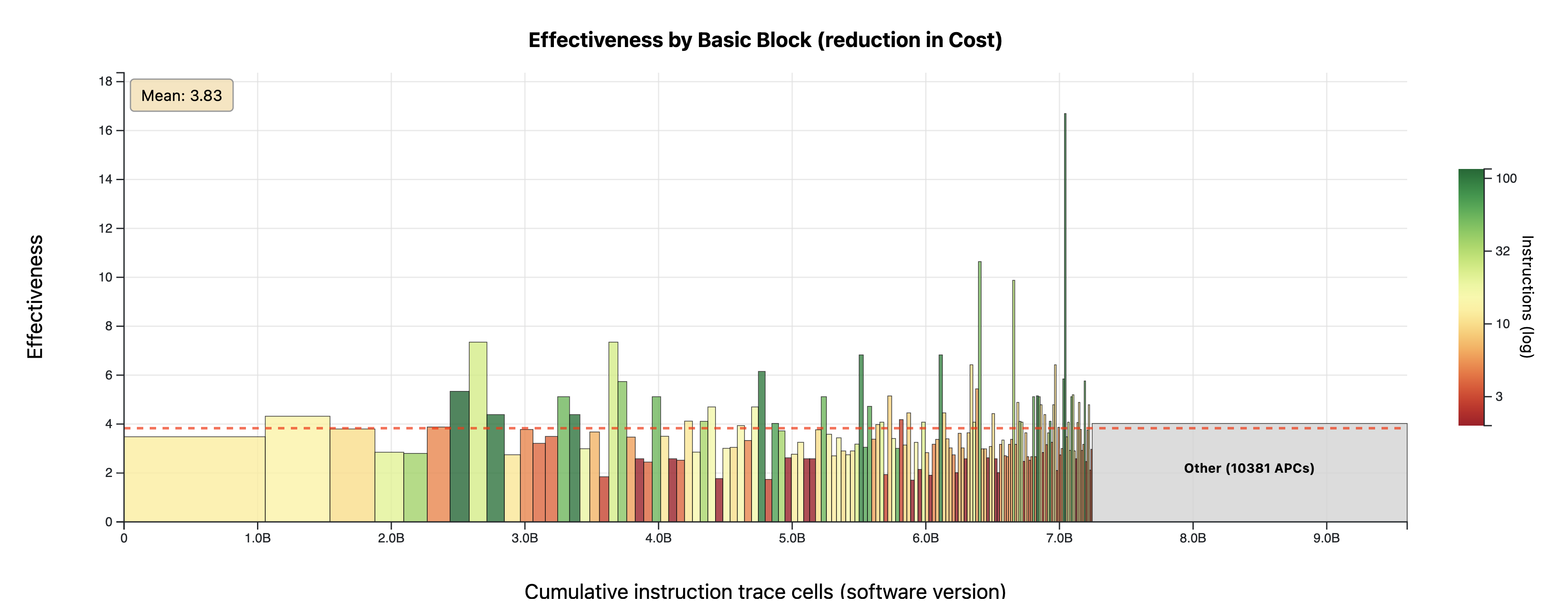

Real-world programs are a lot less structured than the artificial benchmarks above: They are made of tens of thousands of basic blocks, each one executed a different number of times. To explore this data, we developed this viewer, which generates plots like this:

Here, every basic block in the program is a box, sorted by the number of trace cells it causes in the zkVM when run without autoprecompiles. This number also determines the width of the box. The height indicates the "effectiveness", i.e., the factor by which an autoprecompile would reduce that trace area. Finally, the color encodes the number of instructions in that basic block.

Autoprecompiles achieve a close to 4x reduction on average; the exact number depends on the basic block. Autoprecompiles tend to be more effective for larger basic blocks.

To measure the effect of autoprecompiles, we consider two scenarios:

- Manually written precompiles already exist (the state-of-the-art). We apply autoprecompiles only to blocks that are not already accelerated by existing precompiles.

- No manually written precompiles are used.

The results below are based on our fork of OpenVM's reth benchmark. It verifies block 21882667 of Ethereum mainnet, which contains 133 transactions and consumes a bit under 10M gas.

Accelerating beyond OpenVM's precompiles

For this experiment, we report numbers for different amounts of precompiles:

| Number of autoprecompiles | Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than no autoprecompiles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 341.19 | 1.00 |

| 3 | 5 | 293.89 | 1.16 |

| 10 | 5 | 274.16 | 1.24 |

| 30 | 4 | 265.54 | 1.28 |

| 100 | 3 | 248.43 | 1.37 |

Autoprecompiles already provide a 1.37x advantage over using vanilla OpenVM!

However, note that we stop at 100 autoprecompiles, even though we're not yet seeing an increase in proving time as we increase the number of autoprecompiles. This is because beyond 100, the verifier becomes too large for OpenVM's recursion prover.

As mentioned above, this would likely be less of an issue with a different proving system. To simulate this, we report the numbers without recursion also for larger numbers of autoprecompiles:

| Number of autoprecompiles | Segments | App Proof time (s) | Times faster than no autoprecompiles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 232.26 | 1.00 |

| 3 | 5 | 195.78 | 1.19 |

| 10 | 5 | 179.28 | 1.30 |

| 30 | 4 | 174.28 | 1.33 |

| 100 | 3 | 157.62 | 1.47 |

| 500 | 1 | 130.02 | 1.79 |

| 1000 | 1 | 126.35 | 1.84 |

| 2000 | 1 | 128.18 | 1.81 |

With 2000 autoprecompiles, we achieve a 1.81x speedup in app proving time (and even a bit more with only 1000 autoprecompiles). At this point, only 5% of the trace cells are still in RISC-V instruction chips; 62% are in one of OpenVM's precompiles, and 33% are in autoprecompiles. In other words, increasing the number of autoprecompiles further could reduce the number of trace cells by at most 5%.

Accelerating pure software

In this experiment, we removed all OpenVM precompiles from the block verification program, simulating a world where they don't exist at all. We used the modified Rust code to include the base field inversion hint mentioned above.

| Number of autoprecompiles | Segments | Proof time (s) | Times faster than software | Times slower than manual precompile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software | 103 | 4139.00 | 1.00 | 12.13 |

| Manual precompile | 6 | 341.19 | 12.13 | 1.00 |

| Autoprecompiles | 17 | 1577.35 | 2.62 | 4.62 |

We achieve a 2.62x improvement (with recursion) over the hint-accelerated software execution. As ECDSA is a major workload when verifying Ethereum blocks, OpenVM precompiles achieve a better reduction. Note that in this experiment, we are also limited by OpenVM's recursive prover, which puts a bound on the supported number of autoprecompiles.

Conclusion

Let's try to answer the questions asked in the introduction!

How do autoprecompiles stack up against commonly used manually written precompiles? Can we make them obsolete and eliminate a huge amount of engineering effort and security risk?

Probably yes!

For Keccak and U256 acceleration, autoprecompiles perform better than OpenVM's manually written precompiles; for SHA256, our numbers are in the same ballpark. The only exception currently is Elliptic Curve operations. We have shown that the gap there can be significantly reduced by making use of hints and conjecture that the same approach can reduce it further.

What do autoprecompiles add on top of manually written precompiles on real-world workloads, such as Ethereum block verification?

We achieve a 1.37x improvement today with recursion taken into account and a 1.84x improvement considering app proofs only in a single-CPU setup. Assuming that the recursion time for wide AIR tables will improve and that autoprecompiles continue to improve over time, we are confident that we can eventually double the speed of Ethereum block verification with autoprecompiles alone.

Experimental setup: All experiments are run on an Intel® Xeon® Gold 5412U with 256GB of RAM. Note that the reported times exclude witness generation, as we have focused our efforts on optimizing proving time. The raw measurements can be found here: Comparison to OpenVM's precompiles, Reth with manual precompiles and Reth without manual precompiles.